Back at the beginning of January, I started Daf Yomi, a 7.5-year process of reading the Talmud. I’ve been posting about it on my private Facebook page, but decided to also add things here.

This post was originally written on 5 January 2020.

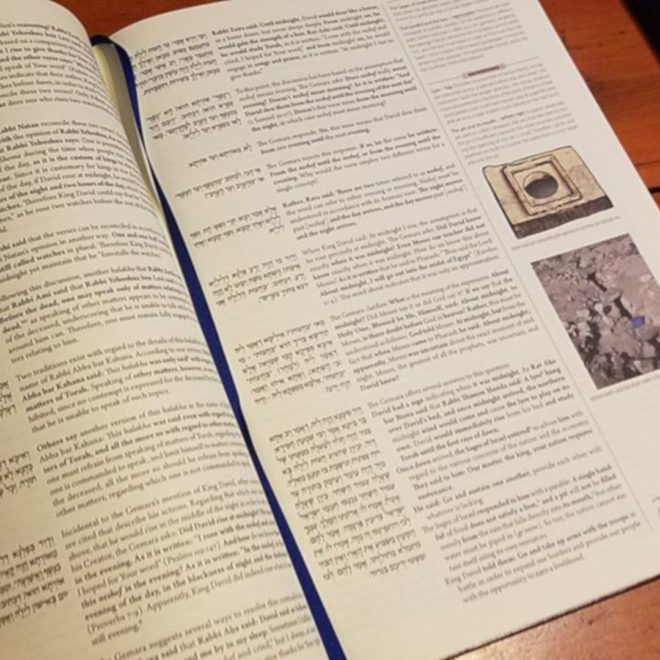

Day 2 of Daf Yomi! Sunday, my child and I went to Shabsi’s Judaica and I picked up the first two volumes of the Koren Talmud Bavli in person, rather than continuing to try to track down copies online (I figure if I get 1 and 2 now, and get 3 when I finish with 1, and so forth, I can avoid the rush). We were very, very clearly the least observant people in the store – the guy checking out next to us was arguing about fringe thickness, which is more esoteric to me than most of the Talmud discussions – but they were very nice to us. I’d been a bit worried, especially since my child presents in a pretty clearly gender-anarchist way. But no need! They even helped me figure out where they kept the just regular bibles with English translations, which was my wife’s and my gift to our kid as they start their B’nei Mitzvah classes this coming Sunday.

Today’s reading is more about when to say the Shema, with a brief diversion into things like whether or not you should be concerned that an empty house might contain demons (you should).

Now that I have a physical copy of the book, I’ve started taking some very light notes in it. I wasn’t sure if I should or not – but then I decided that heck, it’s not a holy book, and it feels very in keeping with the nature of the Talmud for me to maybe pass down a set of books with my comments in the margins.

I found myself with two questions, one technical and one philosophical.

The technical one is, I’m not sure whose “voice” it is when the text says things like “The Gemara responds.” Is that in the Hebrew, or is it a clarification for the English reader? If the former, then what does it mean that one paragraph will say “The Gemara responds…” and then in the next “The Gemara rejects this response…”?

The philosophical one is: a discussion of when King David got up at night to praise G!d (that’s relevant to how many watches the night has, and hence circles back to when the shema should be said) goes on to talk about him telling his army that the way that the nation should sustain itself is by conquering others. In the spirit of not just throwing out texts that I don’t like, I wonder: is there a way to reclaim or reinterpret the imperialism that sits at the heart of so many stories of the Jewish Kingdom? I mean, how do we reconcile it even with the quote from a psalm elsewhere in the notes that enjoins us not to be mean to the poor?