Back at the beginning of January, I started Daf Yomi, a 7.5-year process of reading the Talmud. I’ve been posting about it on my private Facebook page, but decided to also add things here.

This post was originally written on 5 January 2020.

Today, I started the 7.5 year Daf Yomi cycle, reading a page of the Talmud each day. Let’s see if I make it to the end!

It seemed like a meaningful time to start it. My child has really taken to Hinenu, our congregation. Next week, they’ll start B’nei Mitzvah classes. And in about 7.5 years, it will be the summer of 2027. My child is the class of 2026 – when/if I finish this cycle, they will be completing their first year of college. So it feels like the cycle will roughly correspond to the beginning and end of my child’s adolescence.

Which is especially fitting in many ways for me undertaking a slightly over-the-top, slightly pointless, slightly meaningful, engagement with Judaism. Some of you know this story. I left Hebrew school around the age that Ruth is starting it. The joke version of this is that I was driven away from Judaism by Israel and my Rabbi (a true joke). But the immediate impetus was frustration with what we were learning. Having spoken to other members of the sort of diaspora-from-the-diaspora, my experience wasn’t unique: I was taught Hebrew phonetics, so that I could read (in the sense of “make sounds corresponding to sigils”) my Torah portion at by Bar Mitzvah, we occasionally read a Bible story, and then we played a lot of foosball (I was terrible at it). I wanted to talk theology – and that feeling was only heightened when I had a chance to visit my friend’s Reform Hebrew school in the next town over where they did that stuff! It was amazing! I wish I could remember what we talked about, but all I remember was that I was super-excited about it and begged my parents to figure out some way to enroll me in Roundout Valley schools and send me to Hebrew school over there (I know they tried, and it didn’t work). I was the kid who insisted at Passover every year that we read the whole section about “how can it be determined that in Egypt they were smitten with ten plagues but in the Red Sea with fifty?” when Uncle Harry wanted to skip it. So that Reform Hebrew school was my people, and when I made an appointment with my hometown Rabbi to express my frustration and ask if we could do more of that kind of thing, well, his response was “if you don’t like it, no one is making you stay,” and I went home and told my parents I wanted to leave Hebrew school, and that was more or less it for me and Judaism for a really long time.

In later years, now trying to teach young people things, occasionally I think to myself: maybe the Rabbi was just having a bad day that day. Maybe to him I sounded like some of my students who come to me and ask, “but why can’t this class be about MY FAVORITE THING ALL THE TIME?” Maybe he was thinking, jeepers, kid, there are like 20 students we’re trying to teach here and the teachers are mostly sort of volunteers, we’re doing our best. But I’ve talked to my parents and their take was, nah, that Rabbi was always kind of an asshole.

Ironically, it was conversations with my maternal grandparents’ priest (yes, I know that makes me not halachically Jewish) where I was able to scratch that itch for deep discussion about the nature of faith, and G!d, and the universe. I have said (another true joke) that if the Catholicism I encountered through the priest and my grandparents had been more like the social-justice-focused Christianity that I encountered through some of the Jesuits at Georgetown, and later through contacts in the Friends, or even “consistent life ethic” stuff that opposes abortion but also war and capital punishment, I might well be a practicing Catholic today. But while I loved my conversations with the priest, and he did have some clear social justice leanings (I remember my grandmother telling me that she’d yelled at him because he used to put bags of food in the glassed-in porch of the rectory for anyone to come and take if they needed it, and she told him that he couldn’t let “those people” into his house, he’d get murdered), for the most part his perspective was very focused on what we’d now call the right-leaning side of the culture wars, and so even by then I found his theology interesting and his openness to conversation exciting, but he didn’t present a version of Catholicism that would have been compelling to me.

So, the Talmud! My child’s enthusiasm for Hinenu is part of what has me back thinking about Judaism. For years, when we lived in DC and Silver Spring, my wife and I were members of a secular humanist congregation, Machar. I still read about Judaism from time to time, and I’d told my wife that I felt like I couldn’t be a Jew because I was metaphysically an atheist, but that I found a lot of the culture and perspective compelling, so always felt a little sad that I had to read about it as an outsider, effectively. She saw Machar advertised in the Blade, and we went and made great friends, several of whom we keep in touch with still (including the rabbi at the time), and more of whom I regret losing touch with. At the time, SHJ was perfect – it was all the questioning, and social justice stuff, with no commitment to the literal theology. But when we moved, we didn’t have a car, and it was far to get to by bus, and so we kept up with the social justice-y stuff but left Judaism behind again.

My wife, again, heard about Hinenu from social justice friends and contacts, and she and our child attended some of the very early meetings (I had a knack for having other commitments when they were happening). Honestly, what grabbed me was the “yi di di di di,” singing. Don’t know the Hebrew and have trouble following the transliteration? No problem! I mean, this is a killer app – it’s all the ritual of Orthodox Judaism with the low barrier to entry of SHJ! My metaphysics is still probably closer to SHJ than to the Reconstructionist tradition in which our new, great, rabbi is trained, but it was interesting to be able to connect to that aspect of Jewishness in a way that I thought was locked to me. And my child really, really took to it. Plus, I get on with this rabbi better than the old one, and we have a values statement that makes me comfortable with the congregation’s relationship to Israel. For more than a year now, we’ve been regulars at Shabbat services and trying to do better about actually committing to volunteer service (I’ll be at Monday’s safety meeting, I promise!).

So, when the Rabbi posted stuff about Daf Yomi, I was intrigued, and I figured it was the time for me to give it a try.

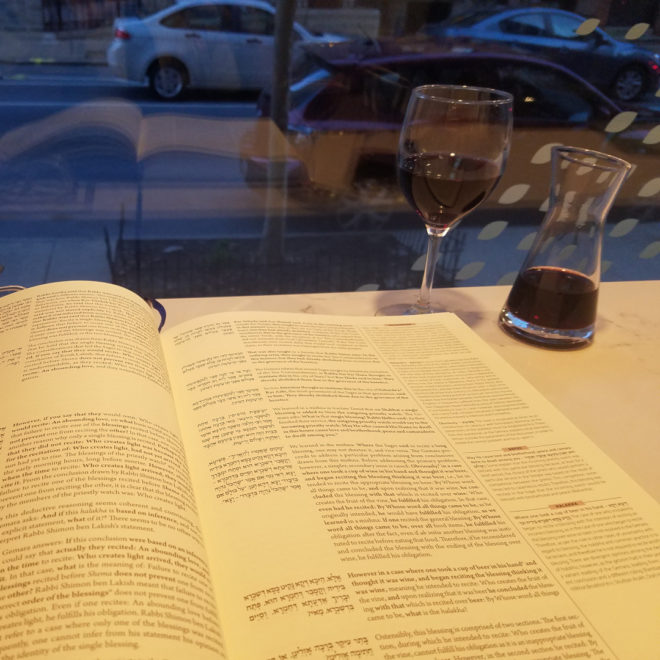

I promised Talmud stuff like nine paragraphs ago, so OK, let’s do that. I’ve ordered myself a copy of vol. 1 of the Koren Talmud Balvi (with the Steinsaltz commentary) but, it turns out, when you decide to do Daf Yomi at the last minute, everyone (including Amazon) will be backordered. So until my copy arrives, I’m using the free online version at Sefaria.

Like Machar, like Hinenu, reading the first page (2a/b) of the Talmud felt like finding my people. First of all, there’s a lot of the “oh, well, it was anger, wrath, indignation, and trouble, a band of evil angels, so each plague was four plagues, or maybe five” content already. “You think that we disagree, but really, what did the rabbis mean when they said, ‘midnight,’ surely not literally the middle of the night, let me explain…”

Plus there’s an element of a more down to earth take: one rabbi says that the window for saying the evening shema starts when the priests go in to eat the offerings made to them by the people. OK, so when is that? Well, one rabbi says, it’s when the stars become visible. OK, says the commentary, jeez, why didn’t he just SAY that? Why put one thing we’re not sure when it happens in terms of ANOTHER thing we’re not sure when it happens, when anyone can look up and see the stars or not?

And the explanation for most of these digressions is then that: well, the digressions are the point. If I say “look at the stars,” OK, we’re done. If I say “when the priests go in to eat their teruma,” then you ask “what’s a teruma?” and now we’ve got four browser tabs open to learn about ritual purification. It’s the way I teach if I’m not being careful (beloved by 10% of my students, the times when 90% of them nap). So again, it feels like a natural thing for me to be reading, even if I don’t actually care that much about precisely when to say the shema or understand half the allusions.

And, true to form for the “actually, in the Red Sea it was 250 plagues” kid, I accidentally read into 3a. Oops! I am sure that somewhere there is a story about the rabbis being so into their conversation that they went further than the allotted time and topics, so I think I’m probably in OK company.

The other thing I noticed about this section is that a lot of it is sort of about the slippage involved in trying to align the social and natural worlds. In a lot of ways, doing so is a compelling ideal – we want to live in complete harmony with both each other and the universe. But it’s not really possible – my alignment of Daf Yomi with my child’s adolescence is a kludge. Sometimes (as in this passage) you’re busy celebrating a wedding and miss midnight so it still feels like “tonight” to you but the encroaching dawn says that it’s maybe in fact “tomorrow morning.” I seem to remember Dante arguing (I thought it was in the Inferno, but now I can’t find it, so probably something else we read in my grad school Dante class) that only G!d, because of omnipotence, can do allegory with actual history. Echoes of the way that, to Kabbalists, the Torah is both a literal record of events and a massive puzzle box revealing the secrets of divine reality.

And maybe this is a mistaken ideal, as comforting as it might be? I think about Dewey talking about habits and society. We come up with various patterns and rituals to meet our baseline needs for things like food and shelter in a way that coordinates with the world and others. And then sometimes those patterns break down so we come up with new patterns and habits to compensate, and so on and so forth until we have complex forms of life, which comprise much of what we find meaningful. Life and meaning and reflection exist because of the slippage between the personal, social, and natural worlds, maybe.

Right at the beginning of the Talmud we get a lesson in how the universe and our social worlds aren’t going to line up properly. Heck, maybe that lesson is built right into Daf Yomi, as well as its starting page – a cycle that’s not a whole number of years? Pages that are several pages long? Not bad for starting from, “hey, uh, rabbi, when should I say this prayer?”

I can’t promise I’ll post about this every day for the next seven years. Heck, Facebook might not be here by then, or we might all have moved on (in mid-2012, I still had a LiveJournal that I updated occasionally), or maybe I’ll move this somewhere else, but for right now it works OK. I certainly won’t post this long about every day, but we’ll see how it goes.